What We're Reading, Vol. 22

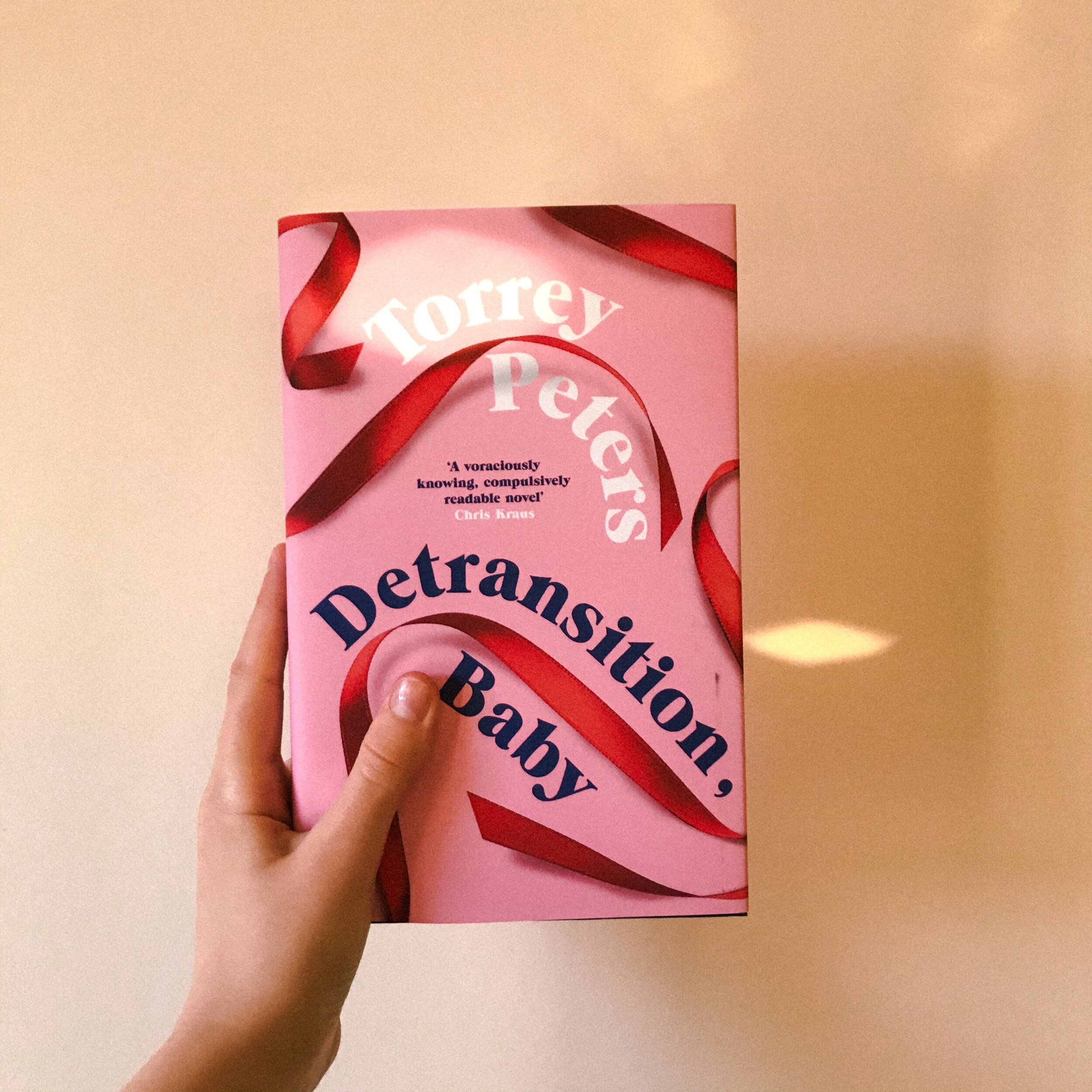

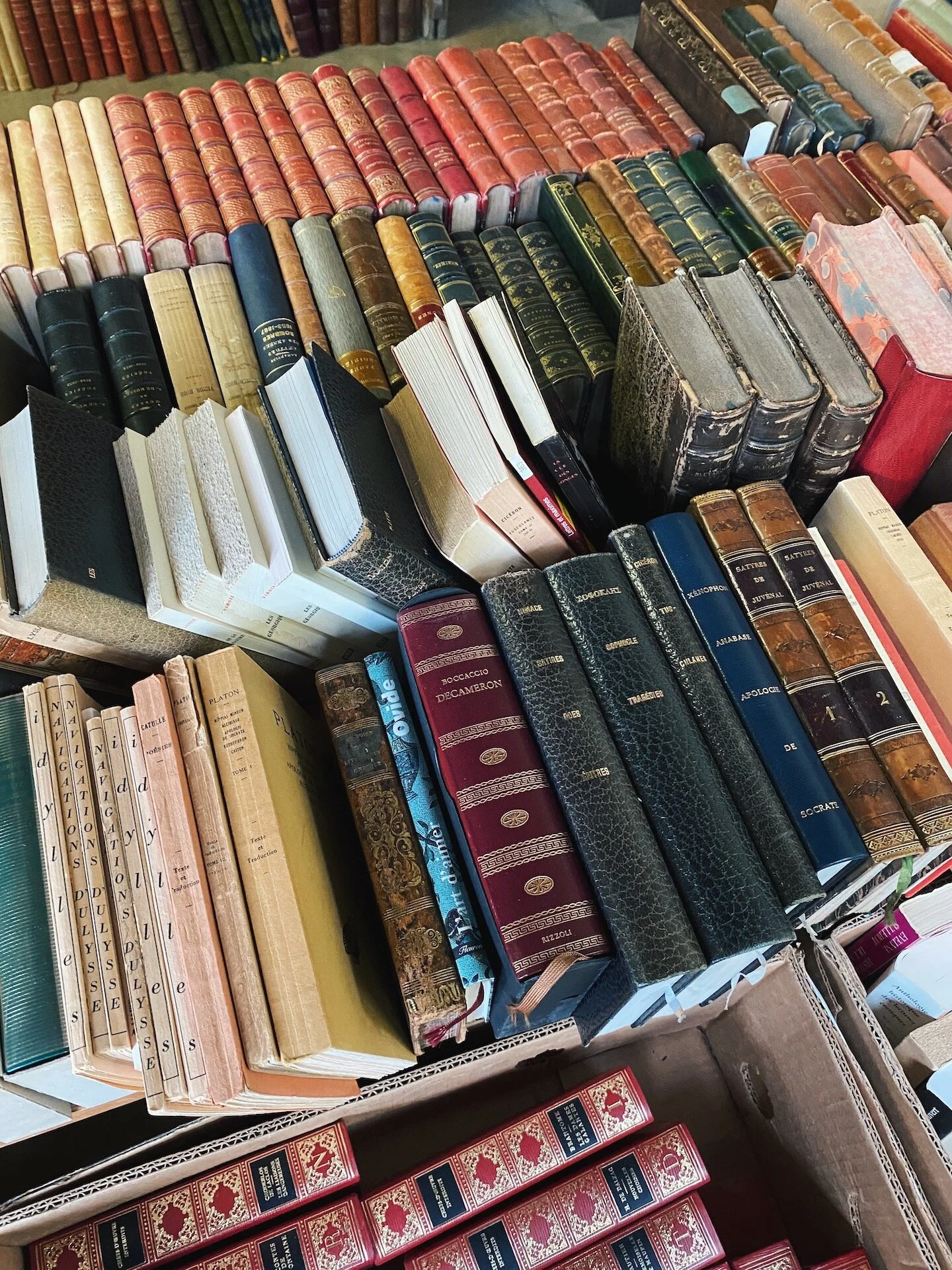

Photo by Madeline Baker.

Like April, this month marches on in the same vein as we continue to do our best amidst the global situation. While the world slowly moves towards reopening, those of us able to remain on the side of caution, and keep to our newly minted indoor lives. For those of us working through piles and piles of things to be read, this month brings on new energy, or perhaps simply new desire, as we pick up as many pages as our arms will allow. Re-reads, new reads, multiple reads at once, we're having them all. Thus, this month's installment of What We're Reading has arrived again in two parts.

As we are prone to follow a good thematic reading list, Part One shared a host of Non-Fiction recommendations. In Part Two, we discuss finally getting over our reading blocks, and all of the unexpected titles that have made it possible, tied to both comforting go-to subjects and genres.

In case you've missed it, we are also now proud to be working with Bookshop, an independent online bookseller supporting local bookstores. We'll continue adding curated lists over time, but for now you can scroll everything from this list and last month's in one easy place.

So, without further ado, here's more of what we're reading this month…

Zoë G. Burnett

As we all try to put ourselves into more comforting spaces, I finally picked up Mark Dery’s 2018 biography, Born to be Posthumous; the Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. You’ve all no doubt seen Gorey’s work on one used paperback cover or another, more likely some branded item sporting the covers of his Gashlycrumb Tinies abecarium. Barring that, perhaps your parents were of the same mind as mine and gave you his anthologies for Christmas, encouraging an already disaffected youthful disposition and prompting phone calls from the guidance counselor. Dery’s analysis goes a step further than others in trying to define Gorey’s amorphous sexuality, which makes sense when analyzed with his ambiguous yet nowhere near explicit work, but sometimes walks a fine line of asexuality erasure. When examining an artist as meticulous and compartmentalized as Gorey, both in life and his work, the push to categorize his sexual designation seems almost invasive. Otherwise, it’s the most comprehensive biography on the author/artist I’ve read yet, covering his manifold contributions to almost every niche cultural facet from the late 1940s to his death in 2000 and emphasizing his often unrecognized influence on contemporary aesthetics and tone. Revisiting Gorey’s books in between chapters has been good fun, and I’m eagerly anticipating the drive down to his small house museum sometime this summer.

Eliza Campbell

Recently I’ve been on a romcom binge, hunting for tropey fun in a genre I usually avoid. I managed to tear through four books in the space of two weeks (largely thanks to quarantine but also the sheer readability of silly romances). From the ones I read, I’d recommend Bridget Jones’ Diary by Helen Fielding and Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan - with their respective films as chasers. Looking forward to the rest of the month, I’m delving even deeper into genre fiction and treating myself to a re-read of The Hunger Games trilogy before the prequel (The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes) is released in late May. Personally, I can’t wait to relive my mid-teens and allow myself to be utterly obsessed with these books.

Mary Hitchman

Time feels suspended. As a furloughed worker I have unfinished business, quite literally, and perhaps this is why I cannot finish a book without picking up another (alright, several others) along the way. Books teeter in piles at my bedside, are strewn across the kitchen table, and have nestled comfortably into the sofa. The lure of starting something new, something fresh, has proven irresistible.

Yesterday I finished Andrea Lawlor’s Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl (which I have been nursing like a daytime pint for nigh on three months) and Little Boy by Lawrence Ferlinghetti. The latter, a book-length prose poem meets stream of consciousness, alternates between otherworldly pretensions and positioning itself uncomfortably close to home. Its 101 year old author hints at several lifetimes well-lived but focuses on more pressing matters: exploitation under capitalism, environmental degradation, and how we strive to fit ourselves into an ever-expanding universe. In many ways, Ferlinghetti’s Little Boy was an unexpectedly perfect companion for Lawlor’s Paul. The eponymous hero’s refuses to be confined or labelled in a defiant celebration of queerness, queer theory, and the perfectly constructed outfit; this proved a welcome antidote to some of Ferlinghetti’s more dated views on gender. Maybe reading books in tandem isn’t so bad? Relatedly, I wonder how Jane Austen would feel about my reading Emma alongside Deborah Harkness’s A Discovery of Witches, which I affectionately call ‘academic Twilight’.

Madeline Baker

I have recovered my ability to read in lockdown, having lost it temporarily to the travails of, well, travail. In very quick succession I have read:

Status Anxiety by Alain de Botton. As relevant now (especially right now) as it was in the mid-2000s I found this an excellent Virgil to guide me through the first circle of lockdown.

At Freddies by Penelope Fitzgerald. Her ear for dialogue and eye for the absurd is as acute as ever, this evokes the 1960s London theatre underworld with relish.

Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante. It’s not often a book makes me blush but this is excoriating - a woman whose husband leaves her in the first line endures a summer alone in a tiny flat with two children and a dog, and the ghost of the abandoned wives she saw around her as a girl in Naples. Profane, furious and a highly accurate dissection of what it feels like to age and love as a woman.

Notes from an Exhibition and Us (Patrick Gale and David Nichols respectively) I’ve grouped these as a pair because I was initially very skeptical about them both, but loved them for the way in which they look at ageing, love and families. ‘Us’ has wit and humour, ‘Notes’ is a very tender drawing of place and relationships shaped by powerful events which remain just out of sight of the main narrative.

In the absence of being able to go places and experience things I’ve reverted to my childhood and experienced them through books. I’ve read a wonderful glossy publication from the Noble Rot bar in London, packed with delectable wines and anecdotes to linger. I’ve torn through John Berger essays about painting, and topped them off with The Pen and the Brush by Anka Muhlstein, which is about how painting shaped late 19thC French novels. This is a blissful read and as an impassioned impressionist fan and an even more impassioned fan of Proust I found this a truly excellent read - light touch, beautifully translated, excellently structured and lovingly researched.

Raquel Reyes

As the pattern follows amongst others here, I’ve mentioned more than once myself recently about how reading has been a struggle for me the last few months, but what I’ve come to realize is that I’ve actually read very little at all this entire year. This is my first WWR entry since January, a large gap I certainly didn’t anticipate. Thankfully, I hope to also be over the slump, as I mentioned in my Comforting Things entry that I have at least this month, managed some consistent reads. I finished Jenny Offill’s Weather, a fragmentary, thrilling apocalypse novel that sort of hit me like a sudden clap. Reading in the form of passing thoughts or glimpses of journal entries, Offill manages to capture so many of the “end times” feelings surging in our atmosphere for so long now, a mix of severity and fear of the unknown, yet walking hand in hand with the realism of everyday life — its sensitivity, petty struggles, moments of quiet hope and humor. I think it will stay with me for some time.

In the same cocktail of climate and struggle and everyday life, I have also devoured My Baby First Birthday, a book of poetry by Jenny Zhang out this month. I was gifted a copy by Tin House and excitedly jumped in after following the glimpses they had teased out on Instagram in anticipation of its release. I think it’s hard to summarize poetry in so many words when poetry itself is usually only so many words, and often additionally limited to a single theme or topic. But Zhang manages to blow through that conception immediately. Womanhood, colonialism, elitism, youth, trauma, loneliness — all are covered in its seasonal chapters, and even love, self love, the love of others and who or why it is owed, as though one should only deserve it. To try and summarize perhaps, I’d say it encompasses the topic of existence, as a person of color raised to believe by the world that they are only worth the parts of a whole that can be exploited by those in power, and the realization that these notions are worthless when confronted. Zhang is fearless in facing those who would shut her out, and delicate when finally reaching out in her narrative’s final pages for those who might be worth connecting to. Raw, funny, and honest, I found myself like Zhang’s contemporary Tommy Pico as he described in a virtual conversation shared to launch the volume, dropping everything to read all the way through because I couldn’t wait to see how it ends.

† This post is not sponsored, however as an affiliate we may receive a small percentage from any purchase made through The Attic On Eighth's Bookshop page at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Reading Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times and Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies, Rachel Tay explores the unease of moving away from one’s own country and language.