Rereading Ali Smith's Autumn

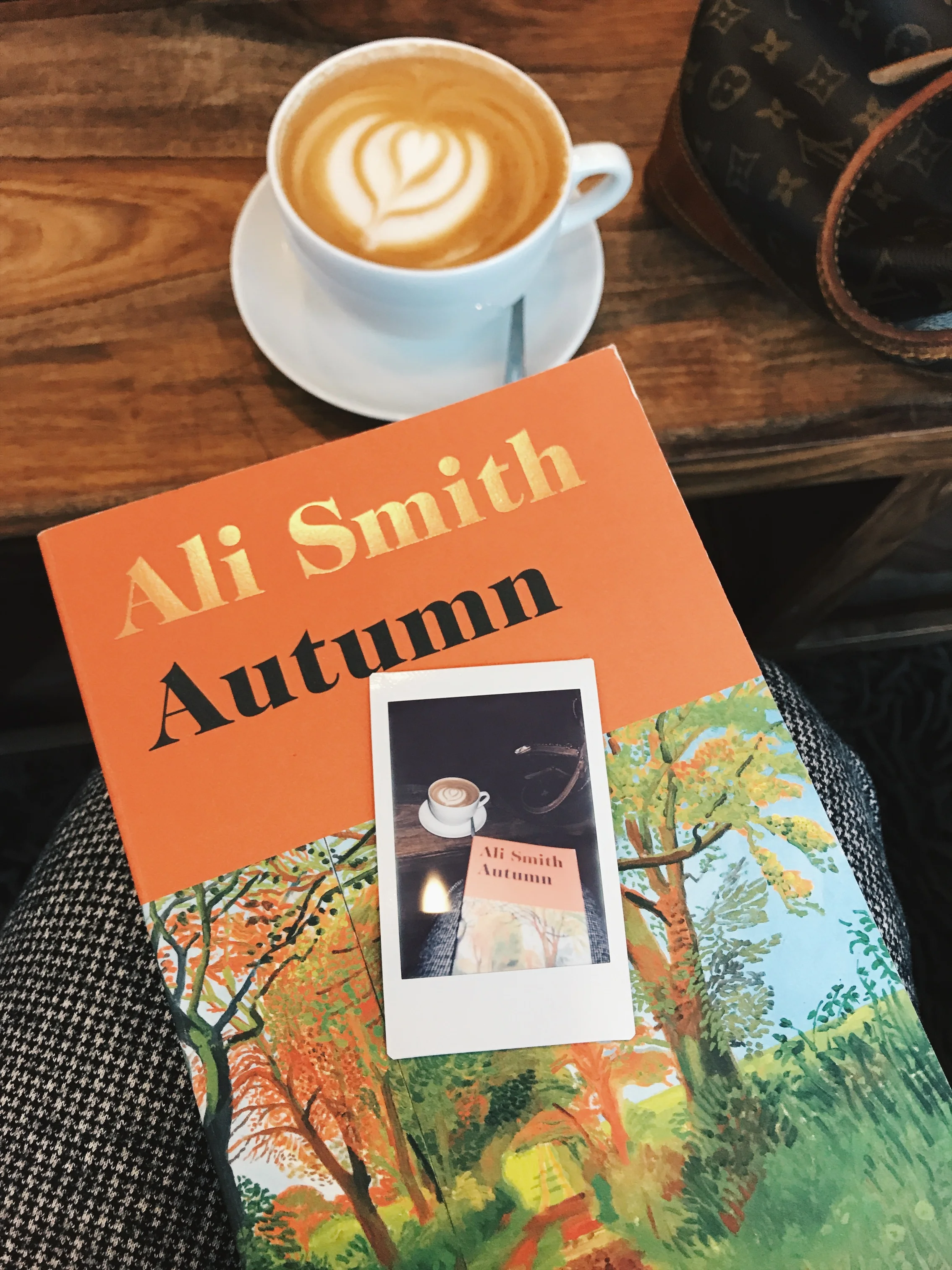

Photo by Olivia Lindem

Rereading literature is a joy dear to most of us here at the Attic on Eighth. In this piece, contributor Rachel Tay revisits Ali Smith’s Autumn in the 2018 season.

Rereading Ali Smith’s Autumn just months after having painstakingly thought and laboured over an academic essay on her previous work, How to be Both, is a curious experience. On one hand, the undeniable parallels between both novels instantly jump out at you — the young and feisty protagonists, the lost works of an artist, the (imperfect) recovering of these lost works in time, etc. — reinforcing your notions of the latter work in one moment, and then challenging your position in the next. The feeling of reading Autumn this way is one of constant consternation. On the other hand, you simply wish for all your critical faculties to just shut up so you could enjoy the novel as you did the first time you read it — all that anger and confusion and hopelessness felt in the midst of a post-Brexit, post-American election world sublimated into Smith’s exquisite meditations on art and memory and transience and humanity. Alas, that original feeling seems rather distant.

So, too, is the summer of 2016, when the novel was written partly as a response to Brexit.

So, too, is December 2016, when Trump was elected, and I delved into the book for the first time.

Shutting down one’s critical sensibilities, what is left is the feeling of laughter bursting through tears — a sort of incredulity, I suppose, epitomised by the very opening of the novel,

It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times. Again. That’s the thing about things. They fall apart. Always have, always will, it’s their nature.

It is a feeble shrug against the immensity of the incessant onslaught of (bad) news that you absolutely cannot get away from, for it’s always going to haunt you on your phone. And thus, for a split second, you find the novel’s later glimpses of optimism almost… twee. But this is not what the novel is about. A dying man centers the focus of the narrative, and you know his time is limited. You know the season of autumn is brief, and soon the harsh bitterness of winter will arrive. You know that those glimmers of hope will be quashed — you know, because you’ve continued living in the two years after the Brexit vote, and watched the world descend into pits of inferno that you’ve never known before. You know that all good things must come to an end, but so does the novel.

It hence concludes with no certain finality. The dying man is still kept alive, and tensions are still kept bubbling; drying leaves cling onto branches, even if only briefly. Teetering between the sunny disposition of summer and a thoroughly depressing winter, Autumn thus allows us — even in today’s political climate — a momentary respite, giving us just enough contentment to trudge on and on, against this increasingly insensible world.

Born and raised in the perpetually summery tropics — that is, Singapore — Rachel Tay wishes she could say her life was just like a still from Call Me By Your Name; tanned boys, peaches, and all. Unfortunately, the only resemblance that her life bears to the film comes in the form of books, albeit ones read in the comfort of air-conditioned cafés, and not the pool, for the heat is sweltering and the humidity unbearable. A fervent turtleneck-wearer and an unrepentant hot coffee-addict, she is thus the ideal self-parodying Literature student, and the complete anti-thesis to tropical life.

Days before its much-anticipated release, Rachel Tay delves into Ali Smith’s Spring