All the Things I Thought I’d Write About

A Note from the Editors: At The Attic we are always sensitive to the world around us, and while we can’t solve the current crisis, we hope to remain a source of calm and comforting escape for our readers. Our content may be less frequent at the moment, but will remain more or less the same in coverage and style. Our submissions will remain open for anyone wishing to take part.

In her first piece for The Attic, writer Sarai Seekamp shares a personal essay on guilt, relational trauma, and acceptance in a continuingly hectic world.

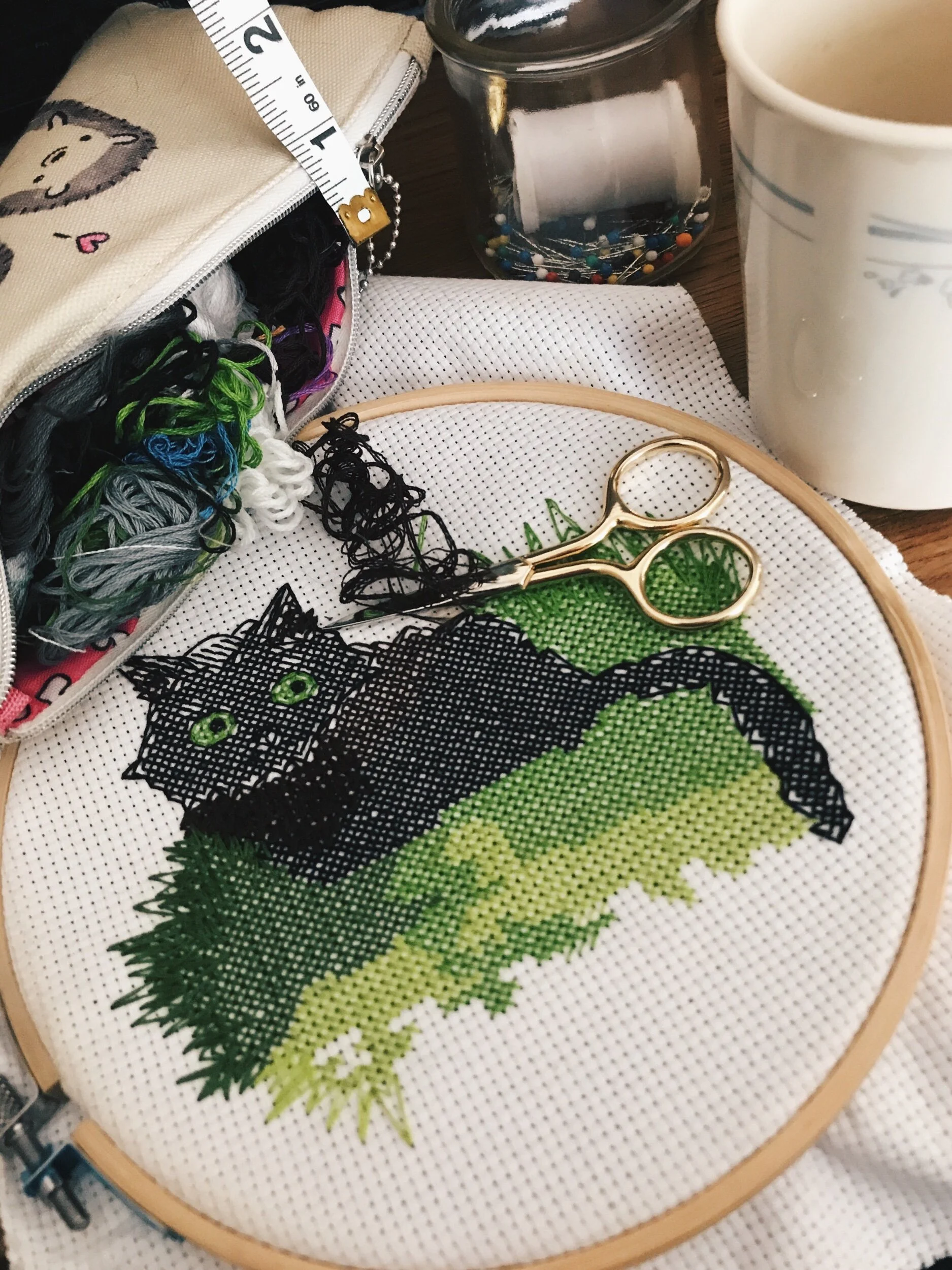

Photo courtesy of Sarai Seekamp.

“I can’t do this”

I began this essay with plans to talk about sadness, frustration, guilt. I will — it’s unavoidable when reflecting on the year so far and all the changes that have come with it. But as it turns out, all I am left wanting to talk about, write about, is what is left after I’ve worn myself out with all those emotions. I have this wholly consuming desire to just be and write and do nothing else. And so, while I was trying to force myself to finish this essay on burnout and guilt, it shifted into me wanting to reflect on my ability to say “I can’t do this” and finding satisfaction in that statement.

First, forgive the seeming “new year, new me” feeling of this all. That is not my intention and I’m not sure if it's at all accurate to categorize this writing as such as this comes so many weeks into a new calendar year. Still, there is no “new me” on the other side of the digital New Year’s Eve 12:00 a.m. that blinks lazily on the stove’s clock just like every other night, or even after the changes that may come during this time of crisis. And, as a side note, why are all digital clocks on stoves green? I digress. This writing has been born from months of work, internal and external, to put a name to those non-singular things that I feel and an attempt to discover the root of it all. It all started with anxiety. Anxiety that feels like the loose ends of the Turkish carpet in the living room getting caught in the roller on the bottom of the vacuum. It feels like sitting on my knees, vacuum upside down in front of me, fingers relentlessly trying to free the strings, and the machine grunting at my audacity. How dare I disturb the nature of this...thing? It was only swallowing up what was placed in front of it, as was its job.

“It feels like sitting on my knees, vacuum upside down in front of me, fingers relentlessly trying to free the strings...”

Maybe that’s not the best analogy for anxiety in general, or even my own anxiety. It’s mutated over the years and only recently has it become a quiet bystander in my life rather than a full-fledged partner, always with one hand on the wheel. It serves its purposes, and my constant worry and attention to the feelings and needs of others was, for a long time, a survival tactic. Those instincts don’t just turn off, but I think it’s been healthier to consider this anxiety as a tool and not just a completely destructive obstacle. I’ve been attempting to think of guilt in the same light, with some help of course.

*

“I can’t do this right now” is, word for word, what I said to my therapist, which was pretty exemplary of what I thought was the problem at hand. I was seated on his couch (which is unfortunately and laughably cliche, though I am pleased to report that I was not lounging or lying on said couch) in his leased office space in Northeast Portland, long before social distancing and self-isolation became the norm, feeling quite literally that I was not capable of doing anything, let alone carrying on the conversation surrounding my guilt, and the fear that underscored it. I was crying, which is not unusual, and unable to articulate what I needed and what I felt in that moment aside from exhaustion and frustration.

When we talk about burnout, we talk about things like a lack of pay, not enough hours in the day, limited resources, and few support services provided by workplaces. We talk about the signs of depression, anxiety, and frustration. We see patterns across age groups, among certain industries, and can break down the likelihood of experiencing burnout based on gender, race, and whether individuals feel like they “have enough time” in the day to complete their work. But I can't talk about those numbers, and quite frankly I’m really tired of talking about data and patterns and trends. It’s easy to remove ourselves from a problem when we quantify it, turn it into graphs and charts. Perhaps that’s just the literature major in me, the writer in me that has always despised algebra and graphing y=x². So, instead, I want to focus on the immediate, the personal, the “I” which is what I always ask my students to do in their writing. Ask yourself: how can you connect this topic to yourself? To your everyday?

“I can only look at my own situation and hope to glean some semi-universal meaning from it.”

I don’t want to get prescriptive. Each situation, each workplace, each experience is different. I can only look at my own situation and hope to glean some semi-universal meaning from it. Last school year, I could count on one hand the days I willingly took off as personal or sick days. This year, I have had to force myself past guilt and self-doubt, to take days off for myself, and not feel the need to explain the whys of it. Last year, I did everything I could to please the people around me as a first-year English teacher, trying to prove my worth. This year, I’ve had to struggle to reconcile my personal values and beliefs with those that exist in our building and have come up wanting. There hasn’t been a week that has gone by this school year when I haven’t felt horribly at a loss, unsure of what to say, what choices to make, when to speak and when to stay quiet and listen. It’s a learning process (ha, see what I did there?) and I’m figuring out, slowly, that while so much of my anxiety and guilt can be attributed to external triggers, that doesn’t mean I’ve lost the ability to change how I react to those triggers.

*

On the Monday before our winter break last year, when two emails went out to the entire staff about needing classroom coverage (followed by a text message from one of our administrators asking me directly to cover a class) I felt all tangled up in that vacuum. I responded to the message, promptly, stating that I was not in the building that day and was not able to cover any classes. My apologies. “Did you let anyone know?” was the response that followed. I was frustrated for a variety of reasons. I was annoyed, because I had, in fact, told the office staff I would be taking the day off and I had filled out the proper paperwork. I was anxious, because I thought that perhaps there was a protocol that I had overlooked relating to telling administration when I was taking personal or sick leave (without the need for a sub, mind you).

I felt ridiculous, for texting my mentor clarifying that I, as a grown-ass woman who rarely takes time off from the high school, did not have to ask permission to take personal or sick days. She confirmed that no, I could take days whenever as long as I requested a sub. I was angry, because a lot of the male coordinators in our building seldom get asked to pick up the slack to cover classes or go on field trips at the same rate that I or the other female coordinators do. I felt guilty because I wasn’t there to cover a class, to say yes, even though if I had been in the building that day, I undoubtedly would have had plenty of my own work to complete. I would have wanted to say no while saying yes. This range of emotions all happened within a few moments before I had responded with “My apologies.” Recounting to my therapist those feelings and thoughts in the moments after receiving the emails and texts hit a nerve. Specifically, it hit the “you are not doing enough, people are going to be disappointed in you” nerve followed by the “why the hell are you allowing yourself to get so worked up over this?” nerve.

“The guilt when I “failed” had become automatic thoughts, feelings, and actions.”

During that same session, my therapist and I talked about relational trauma, and how it was manifesting in my life. Specifically, he was talking about how the relational trauma I had experienced, my anxiety associated with pleasing the adults around me, and the guilt when I “failed” had become automatic thoughts, feelings, and actions. My therapist has always done a phenomenal job of relating information that could potentially trigger this so-called vacuum anxiety in an informational, thoughtful way, and often-times through an educational lens. In this conversation, he was encouraging me to consider what felt familiar about this situation? He asked, “How old is the part of you that feels guilty when others are displeased with you? How old is the part of you that never says no just to keep people from being disappointed or angry with you?” He wanted me to consider that this “part of me” was a separate being, someone who was young and just trying to operate and survive in a high-stress, unstable home, and was now not a part that needed to be involved in my day-to-day life. I could function without it and I could tell “her” to take a step back.

This is when I started crying. There have been so many moments this year when I have come to this point of utter exhaustion and frustration, unwilling and unable to move forward.

“I’ve spent the better part of the year dwelling on the ways that I feel exhausted, frustrated, angry, drained, and guilty.”

A week later, I found myself in a yoga class, for the first time in years, and trying really hard not to focus on how my right hip is throbbing, which I realized absolutely should not be happening. I mean, I’m only twenty-six and a former athlete and I’m healthy. So why the hell are my hips in so much damn pain? But they are. Specifically my right hip, and it’s really difficult to get my body to do the low lunge and twist into the… well, I forget the names for all the positions, but it involves a lot of twisting. In any case, during this first yoga session at a place I’d never been, with people I had never met, the instructor “suggested” that we set an intention for ourselves. All I could think of wanting for myself was happiness.

So, in all of those moments, when the instructor suggested we set an intention, or come back to the one we had set earlier in the class, I told myself I just wanted to be happy. It wasn’t easy to focus on that intention while breathing and twisting my body into shapes it hadn’t been in before. It wasn’t easy finding those places I was able to soften. But I tried. And maybe that’s why finishing this essay has been so difficult. I’ve spent the better part of the year dwelling on the ways that I feel exhausted, frustrated, angry, drained, and guilty. In that deep lunge, trying to keep my legs from totally collapsing beneath me, I realized I was tired of being frustrated all the time.

*

And this essay wasn’t going to just be about work, right? It’s almost always about something more. Sure, I’ve spent a majority of my time untangling the threads from the vacuum in my classroom, with the door closed, at my desk, trying really damn hard not to cry because my students were mad at me, or my athletes were quitting, or my coworkers were saying and doing things that I adamantly did not align with, or I was being asked time and time and time again to fill in, step up, take over, fix...and it all became too much. I didn’t have enough hours in my day, I didn’t have enough money to pay for an endless supply of snacks to keep in my room to feed hungry children, I didn’t have all the patience and grace to find a more compassionate lens with which to view my fellow educators, coaches, and adults. I just didn’t have enough. I felt guilty about that, just like I felt guilty about taking a personal day for myself and being unable to say “yes” to covering one more class. And I felt guilty that I couldn’t keep pushing through my frustration, my sadness, my anxiety, and got to the point where I had to say “I can’t do this.”

“I needed to say it out loud because I never say it out loud.”

But that’s just it. I couldn’t and it was okay, and I needed to say it out loud because I never say it out loud. I can’t remember a time that I have ever acknowledged an inability to do something, whether it was true or not. There was simply never admitting that I couldn’t handle something, anything. At that moment, in my therapist’s office, on my personal day off work, I needed to stop. I needed to say “I can’t do this” and just let that be true and not get swallowed up by the guilt of it.

So it’s not just about work. It started there, just like everything in my life has started with school and with work (which is school). And then it spirals out until I’m shown the connections either by my therapist or my friends, the ones who know me the best who don’t let my nonsense slide because they love me. I’m reminded that it’s not just about my work, all this guilt, all this anxiety. It’s about everything. Relational trauma and burnout and anxiety and guilt seeps into everything. Maybe it’s a good thing because it helps you survive when you need to; it helps you to get to a space where you can take a step back. And when I start to examine the frustrations with my work, it’s easier to carve up that first layer to get to what’s underneath and say “okay, well where does this apply to my day to day and my relationships.” And this is hard. And it hurts. But it also feels really damn good to let go of some of these unhealthy coping mechanisms. The ones that keep me up most nights, that make me want to melt into the floor of my classroom and not get up again, that make me seek acceptance and reassurance from people who shouldn’t have that sway over my worth.

Reflecting on all that this essay was meant to be, all the things I thought I’d write about, I realize that I actually did end up exactly where I planned to in the first place. I reminded myself that saying “I can’t do this” isn’t so hard after you do it the first time completely wrecked on the couch in your therapist’s office (sitting, not lounging) on your personal day. I reminded myself that setting the intention to just be happy, in a yoga class while your hips are burning, can be a pretty damn good way to start moving past all the frustration, guilt, and anxiety. And while the world feels swallowed up by this unprecedented health crisis, and my hours are consumed with trying to connect with my students and their families as schools close, I find that it is a perfect reminder to take a step back and find joy in the small moments when I get the chance.

As a high school English teacher in Portland, Oregon, Sarai Seekamp often finds herself wearing many different hats. After graduating from the University of Portland with a B.A. in English Literature and the University of Southern California with a M.A.T. in Secondary Language Arts, she has spent the past few years writing at her website scienceofluck.com and helping her students find ways of expressing themselves both in and out of the classroom. When she isn't writing or teaching, Sarai enjoys traveling to Ireland and the UK, cuddling with her cats Osha and Sally, and working to change the ways young women experience the world of athletics through her high school's track and field program as the Head Coach. Who says you can't do it all?

The five things we’re doing to make the most of February 2021 to reconnect with both ourselves and our loved ones after a long winter.